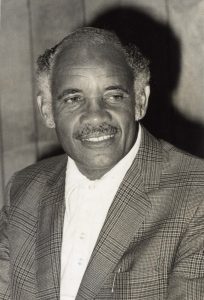

George Simkins

By Steve Huffman

Gillespie Golf Course is recognized as a tight nine-hole tract, as good a municipal course as you’ll find.

It’s also recognized as the site of one of the battles in the civil rights movement, a place where a group of black men sought to integrate a course they weren’t allowed to play.

The resulting legal fight went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court.

“I’ve tried to grasp how this course was involved in a case that went all the way to the Supreme Court,” said Bob Brooks, Gillespie’s director of golf, referring to the civil rights case for which the course is greatly remembered.

“Although the original 18-hole Perry Maxwell golf course was sacrificed as a result of anger, the end result is so much greater in that it made golf accessible to so many others,” added Brooks.

The case dates to Dec. 7, 1955, when six men – Phillip Cook, Elijah Herring, Samuel Murray, George Simkins, Joseph Sturdivant and Leon Wolfe – entered the pro shop at Gillespie and asked to play.

Simkins, who died in 2001, was the last surviving member of the group and its most well-known. He was a local dentist and for years headed the Greensboro branch of the NAACP.

The civil rights movement was just beginning to gain traction in the South in 1955. Six days before Simkins and the others attempted to integrate Gillespie, Rosa Parks had refused to give up her seat to a white man in Montgomery, Ala., leading to a bus boycott there.

When Simkins and his cohorts attempted to play at Gillespie, the pro shop attendant snatched the registration book from them. Gillespie, a course that belonged to the City of Greensboro and was built primarily through taxpayers’ money, was at the time operated as a private facility.

It was leased from the city by a group of white citizens, a lease-agreement common in Southern municipalities. It was a means that circumvented the Supreme Court ruling that made it unlawful for city-owned courses to discriminate.

Despite being refused the right to register, members of “The Greensboro Six” — the name by which the group would come to be known — placed their 75-cent greens fees on the pro shop counter and headed to the first tee. Ernie Edwards, Gillespie’s pro, caught up with them, ordered them off the course and threatened to have them arrested.

They ignored Edwards and played nine holes before leaving. That night, each was arrested for trespassing, then taken to jail where they posted bonds.

All were charged with trespassing on a private course despite the fact that Gillespie was owned by the city and white “non-members” were allowed to play with few questions asked. Blacks were turned away as non-members.

Those charged were found guilty of trespassing, fined and ordered to spend 30 days in jail. A second trial was ordered because arrest warrants had been altered to call Gillespie a “club” instead of a “course.” Again, the men were found guilty.

The case was appealed to the North Carolina Supreme Court, but before being heard there, Middle District Court Judge Johnson J. Hayes of North Wilkesboro gave the men a strong declaratory judgment, calling the “so-called lease” as a private facility invalid.

Hayes ruled the plaintiffs were unlawfully denied access to the course because of their race and said he planned to open the course to all citizens.

“The golf club permits white people to play without being members, except it requires the prepayment of green fees,” Hayes wrote. “The plaintiffs here paid their fees, were forced off the course by being arrested for trespass.”

The statement and evidence from Hayes, however, were omitted from the record presented to the state Supreme Court, which denied the criminal appeal. Simkins would later say the omission essentially doomed the case when it was presented to the U.S. Supreme Court in 1958, which ruled 5-4 against the Greensboro Six.

A strong dissenting opinion by Chief Justice Earl Warren prompted North Carolina Gov. Luther Hodges to commute the jail sentences of the plaintiffs.

“There were some strange decisions up and down the line on that case,” said Greensboro’s Henry Frye, the first black chief justice of the N.C. Supreme Court

Frye, now 83, lives not far from Gillespie. He plays the course an average of twice a week. Frye said he loves Gillespie.

But Frye is equally quick to note that actions like those that played out at Gillespie were the norm, not the exception, for the era. Before Simkins attempted to integrate Gillespie, the city built a nine-hole course for blacks, Nocho Park. Those who played it said it was a poor excuse for a golf course, and reeked of odors from an adjoining sewer treatment facility.

“They were supposed to be the days of separate, but equal,” Frye said. “I called them, ‘Separate, but unequal.’”

Bill Hill grew up not far from Gillespie and caddied at the course as a teenager. Now 72, Hill remembers that while most of the caddies at Gillespie were black, none of the golfers were.

“The members didn’t want to play with blacks,” Hill said, “but they didn’t mind us caddying for them.”

Clyde Blount enrolled at North Carolina A&T soon after graduating high school, then dropped out and worked 40 years before returning to Guilford College and earning a bachelor’s degree. He followed that with a masters from A&T.

For his senior thesis at Guilford, Blount wrote about Simkins and his fight for justice. Blount said Simkins was his dentist (he still refers to him as “Doc”) but he knew little about his efforts to integrate Gillespie until after he died.

“He was a fireball, he was involved in all sorts of things,” Blount said. “I started playing golf at Gillespie in ’73 or ’74, and sometimes I’d see Doc out there in his dental garb. He’d come straight from his office.”

In the late ’50s, when Gillespie was ordered to desegregate, someone set fire to the clubhouse and destroyed it. City leaders opted to close the course and get out of the business of golf. During that time, property on which nine of the 18 holes stretched was sold.

Gillespie finally reopened as a nine-hole tract in 1962.

Appropriately, Simkins was the first to tee off the day of the reopening.