By Brad King

Fittingly in many ways, legendary Wake Forest University golf coach Jesse Haddock passed away during the week of the Arnold Palmer Invitational.

Though he never coached Palmer during his historic, three-decade stint at Wake Forest, the program Haddock inherited in 1960 always benefited from The King’s cachet.

Shortly after assuming control of the Demon Deacon golf team, Haddock turned to Palmer, a former Wake Forest golfer who was by then making a worldwide name for himself on the PGA Tour, and asked him to assist the sagging program by funding a scholarship.

“Arnold gave us $500,” Haddock said, “and we were on our way.”

Palmer’s scholarship helped pave the way for Haddock to recruit many of the 63 golfers who would achieve All-American status during his record-setting 32 years at the helm of the Atlantic Coast Conference golfing dynasty.

From 1960 until he retired in 1992, Haddock’s team captured three national championships (1974, 1975 and 1986) and finished runner-up another three times. They also won 15 ACC titles, including an amazing run of 10 straight from 1967-76. Haddock was named national coach of the year three times.

“We have the best school in the South,” Haddock would tell recruits and he meant every word. He truly bled the black and gold.

“Wake Forest College was a perfect place for him for there were dozens of young men just like him, who came with limited means and unlimited dreams,” said Bill Joyner, a retired Wake Forest Senior VP and one of Haddock’s closest friends. “None were more hopeful than Jesse.”

Haddock celebrated his 91st birthday in January, yet his health was declining and he was admitted into hospice soon thereafter. He died peacefully the morning of March 14, his wife of 68 years, Kay, and one of their daughters, Dottie Kay Hill, by his side.

Five days following his passing, Haddock was honored at Wait Chapel on the Wake Forest campus with a service attended not only by many of his former players — his “boys” as Haddock lovingly called them — but many golfers who were influenced by his legacy, as well as other former Wake Forest athletes and employees.

A day forecasted as rainy and cold appropriately turned out sunny and pleasant: a perfect afternoon for golf. The altar flowers were black and gold, while the magnolia leaves were handpicked from the old campus in the town of Wake Forest.

Nine former players — John Morrow, Jack Lewis, Jay Sigel, Jerry Haas, Loge Jackson, Joe Inman, Billy Andrade, Gary Hallberg and Scott Hoch — served as pallbearers, while all of Haddock’s former players were recognized as honorary pallbearers. Joyner made opening comments followed by speeches from four other former players: Curtis Strange, John Buczek, Mike Brown and Lanny Wadkins.

“I know Coach is up there with Arnold,” said Buczek, one of Haddock’s first great players and later a legendary PGA professional. “Arnold, with that great smile of his, is greeting Jesse and saying: ‘Job well done.’”

Like Palmer, Haddock was a man of the people.

“We would go to tournaments,” Wadkins said. “Every player at every other school would come up and say ‘hi’ to Coach. It was amazing how many other players at other schools respected and loved Jesse Haddock. When you were with Coach, you knew you were with somebody special. He was definitely one of a kind.”

“He had an unbelievable talent for remembering people’s names,” Jackson said. “He remembered everybody’s name and I’m not talking about just his golfers. If he ever met you, he would know who you were next time he saw you and ask you how your wife was doing by name. I’ve never known anybody quite like that.”

“Coach gave me my greatest gift … a chance,” said Strange, his voice cracking. “My dad had been gone four years when I showed up at Wake, so personally Coach was my father figure and mentor for my three years here in Winston. I respected him so much and hung on to every word.”

Unlike Palmer, Haddock was a mediocre golfer at best. He didn’t take up the game until the year before he took over the golf program. “He didn’t know much about the swing,” Jay Haas said. “But he knew what made people tick.”

“His strength was he was a really, really good mental coach,” Jackson said. “He was sharp enough that he would watch a player all the time and he would know what he was doing when he played well, so when you started playing poorly he could pull you aside and tell you what you were doing different. That was a very easy way to get back on track.”

“Coach Haddock was a true innovator in sports psychology,” said current Demon Deacon golf coach Jerry Haas, another of Haddock’s former players. “He was a master at handling players and knowing all the right buttons to push. He was strong and tenacious and he expected that from his players.”

“He got them to be great when it counted,” added former N.C. State coach Richard Sykes.

Haddock famously hated long hair and facial hair. “We’re going to look better, act better and play better than our competition,” he told his players.

One year, a highly recruited freshman arrived on the Wake Forest campus sporting an impressive moustache. Haddock offered to show the newcomer and his teammates the Wake Forest “Wall of Fame” featuring framed photos of some of the program’s best players: Palmer, Billy Joe Patton, Sigel, Jack Lewis, Wadkins and others.

After he got through a dozen players, Haddock asked, “Anybody seen a moustache yet?”

“Nobody said a word,” Jackson recalled. “But the next day when the kid showed up he was the cleanest shaven guy you’ve ever seen in your life with a fresh haircut.”

A tobacco farm boy from Pitt County who grew up in the heart of the Depression, Haddock first set foot on the old campus in the town of Wake Forest in 1944 for what proved a short visit. He was drafted shortly thereafter and spent the closing days of World War II in Germany with the Third Army.

Haddock returned to Wake Forest in 1947 and never left. He took a job in the athletic department to help pay for his education, running errands for athletic director Jim Weaver and basketball coach Murray Greason, while driving around legendary Wake Forest football coach Peahead Walker.

In 1952, Haddock became the first in his family to graduate from college.

Business degree in hand, Haddock began to rise through the ranks of the Wake Forest athletic department. When Horace “Bones” McKinney found that coaching the Wake Forest golf team took up too much of his basketball time, he turned it over to Haddock, who was then an assistant athletic director.

From that point on, Haddock would define the role of collegiate golf coach in the modern era — putting the Demon Deacons’ golf team on the national map and molding the early careers of many future greats. Twenty of Haddock’s players would go on to play on the PGA Tour and 15 on the Champions Tour.

The program’s first national title came in 1974 when Strange, a 17-year-old freshman, drained a slick, downhill putt for eagle on the final hole to clinch the championship.

The following year’s squad, led by Strange and Wadkins — along with second-team All-American Bob Byman and third-team All-American David Thore — may have been the greatest team in college golf history. The Demon Deacons won seven of nine tournaments that season with an average margin of victory of 27 strokes and won the NCAA title by 33 strokes, shattering the previous record of 19 and causing tournament officials to restructure the way they ran the championship. Wake Forest’s dominance in the 1970s even forced other ACC schools to upgrade their programs to avoid such embarrassment.

“Coach molded us into a family,” Strange said. “Family and team always came before individual success.”

“We carried ourselves and we played a lot of good golf because we were representing him and Wake Forest,” Wadkins said. “I think it was in that order. He was always there for all of us.”

Every year when April rolled around, Haddock would hold court under the old oak tree outside the Augusta National clubhouse. In 1988, Wake Forest produced nearly a quarter of the field that made the cut at the Masters. “To stand under that oak tree at Augusta National with Jesse was like standing on the porch of the Vatican with the Pope,” Joyner said. “I met Vice President Quayle and Nancy Lopez within 15 minutes of one another. And they came to meet Jesse.”

In his later years at Wake Forest, the Haddock’s started the Jesse Haddock Golf Camp. Young golfers came from all over the world to learn the finer points of the game from Coach Haddock and many of his players. “Beyond our Wake Forest golf team family, he touched so many young lives literally across the world,” Brown said.

Haddock was known as a gifted conversationalist and he loved keeping up with his boys. Jackson once told Strange he should call Coach because he hadn’t heard from him in a while. “Give him a call when you have a spare 45 (minutes),” Jackson said.

“They were always the nicest conversations,” Strange said, “because he would just reminisce.

“People have called him a mentor, teacher and father figure,” Strange said. “He was — and much more.”

“He spent five decades of his life teaching, mentoring, offering words of wisdom that apply on and off the course, and instilling confidence in us,” said Buczek. “He loved his boys.”

Following his retirement, Haddock and Kay briefly moved to Florida to be near their daughter, Sherry, who was suffering from cancer and her husband Jim Simons. After Sherry’s death, the Haddock’s took the three Simons boys under their wings, forever changing their lives.

“He was devoted to shaping the lives of the young men entrusted to his care,” said Wake Forest President Dr. Nathan Hatch.

Haddock was later enshrined in the Wake Forest University Sports Hall of Fame, the North Carolina Sports Hall of Fame, the Carolinas Golf Hall of Fame and the National Golf Coaches Association Hall of Fame.

He and Kay were longtime fixtures for Sunday brunch at the same table at Old Town Club, Winston-Salem’s bastion of southern gentility and the longtime home course of the Wake Forest golf teams. “He enjoyed coming out there and seeing people,” Jackson said. “I think it was a good way for him to stay in touch with the past.”

Despite suffering a pair of strokes five years earlier, Haddock seemed to recover fully and he drove his car up until the last year of his life.

Several years ago, however, Haddock confided in Jackson that he didn’t feel comfortable going out to Old Town anymore.

“I’m just getting to where I forget people’s names,” Haddock told Jackson.

“Coach, on your worst day you remember more people’s names than anyone I’ve ever met on their best day,” Jackson told him.

Following the service at Wait Chapel, there was a reception for family, special friends and former players at the Haddock House, a $4.5 million state-of-the-art on-campus facility that is part of the Arnold Palmer Golf Complex, dedicated in Haddock’s honor two years ago.

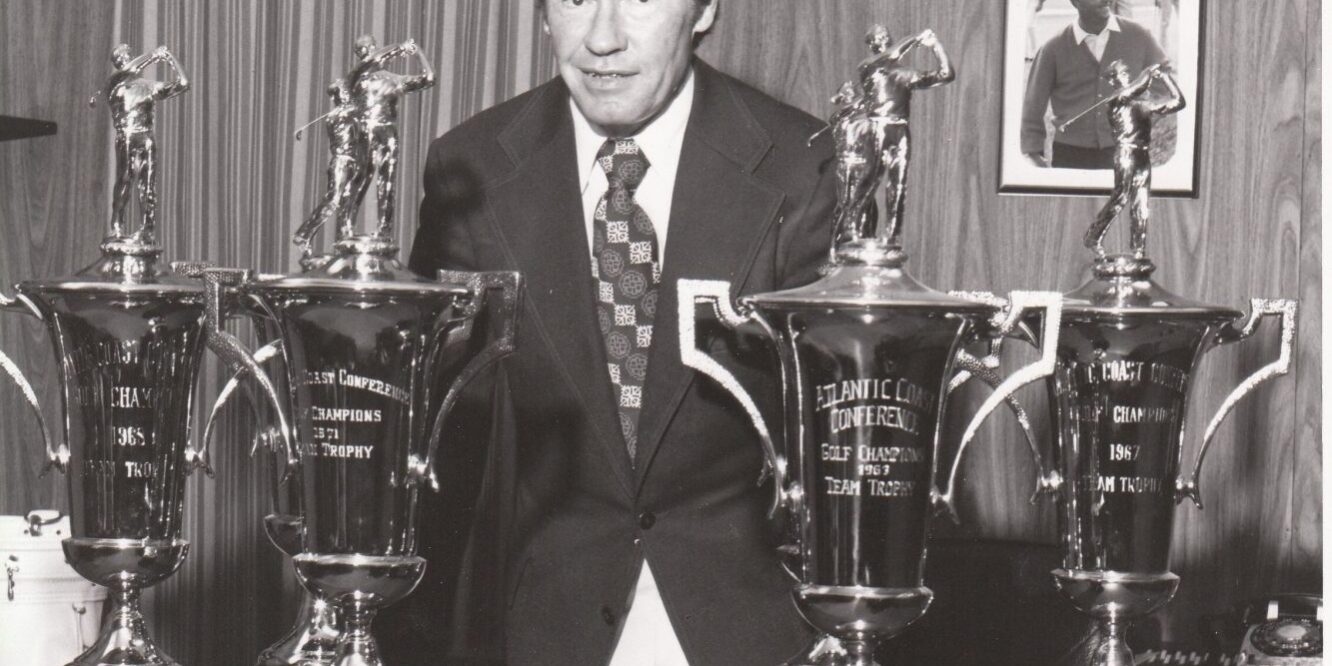

The lobby features a large glass display case with championship trophies; wall displays honoring Haddock and Palmer, and a space to commemorate NCAA All-Americans. In the heritage room, visitors can view trophies and search via interactive touch screens to see Hall of Fame members, championship teams, and videos of Demon Deacon greats going back to the 1950s.

A fitting monument for a Coach’s life well led.

“Coach Haddock embodied what coaching is,” Jerry Haas said. “He was there for the players, but he let you become your own man.”